This article, written by Philip Girvan, StFXAUT Communications Officer, appears in the Summer 2019 edition of The Beacon.

Dr. Teresa MacNeil describes the Antigonish Movement as being “in my blood”. The Extension Department had a tremendous influence in rural Cape Breton while MacNeil was growing up during the 1940s and 1950s, and its ethos has driven her ever since. In an interview with The Beacon, MacNeil described getting caught up in it:

The whole philosophy of people trying to do something to better themselves because they had no choice really that was the only show in town: that they do something themselves. So as a young person you just got into all that swing. So I went to kitchen meetings when I was a teenager and that sort of thing.It was part of my belief system.

While an undergraduate at StFX (BSc. 1957), MacNeil was involved with the student co-op and also volunteered with the Extension Department. This experience contributed to Father Michael J. MacKinnon, the then Director of Extension, recommending her for the position of Education Director of the Grand Falls Cooperative Society. While in Newfoundland, MacNeil served in this capacity and other roles, including extension work with the Newfoundland Department of Education, before the StFX Extension Department then hired her to work in the Sydney office.

After a few years in Sydney, MacNeil moved to Madison to pursue graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin (M.S., 1965; Ph.D., 1970). In July 1970, MacNeil arrived in Antigonish, having been recruited several months earlier to lead StFX’s newly established Department of Adult Education.

The Department was unique, but administration had confidence in MacNeil, the team that she had assembled, and the curriculum that they developed. Ten years or so into her Chairship, MacNeil met with John Sears, the then StFX Dean of Arts and her immediate supervisor. MacNeil recalled the conversation: “I thanked him because we made a lot of changes. I thanked him for his help and his answer was, ‘I never understood what you were doing; I just trusted you’. I really, really appreciated that. That was kind of the mood at the time”.

MacNeil spent twelve years with the Department of Adult Education before succeeding Father George Topshee as Director of the Extension Department in 1982. MacNeil was both the first woman and the first lay Director of Extension. She arrived at a challenging time. Historian Peter Ludlow (2018) described Extension at that point as “trapped by its history” as well as “desperate to find ways to serve the community while remaining true to principles 1 ”.

MacNeil was intrigued by these challenges. Organization was the underlying principle during Extension’s early days. The creation of credit unions, the formation of labour unions, and the establishment of consumer, producer, housing, and credit cooperatives had made a huge difference in people’s lives. However, by 1982, these institutions had become self-sufficient and did not need, nor particularly want, help from the Extension Department.

Meanwhile, the role of government had expanded. Civil servants had been hired to do much of the work that extension staff and volunteers had done in fisheries, labour, and housing. Topshee had lamented the need to chase government grants, and had suggested that fulfilling the mission would require a multi-million dollar endowment fund. Although certain programs delivered revenue, MacNeil struggled to raise the funds necessary to run the Department.

In the context of the Antigonish Movement, adult education, according to Dodaro and Pluta, “was a combination of study and research aimed at building up the entrepreneurial capacity to foster economic action and the required expertise to administer the institutions that were created” 2(2012; p.269). Under MacNeil, adult education would no longer just be seen as a tool toward socio-economic development; it was to become the principal objective of the Department:

I wanted to go to Extension because I really believed that that could be a way to have people carefully identify what they were up against, and take measures to systematically overcome those hurdles. Take the adult education model again because that’s what it should be and say, “All right, so I’m having a hell of a time in Guysborough County with the fact that the inshore fishery is just collapsing, let’s say the cod fishery, so how am I going to take what I have, because I have skills as a fisherman, and make something of it. That’s how I saw the Extension Department working.

It was a difficult balancing act: adhering to Extension’s guiding philosophy, which might be summed up by M.M. Coady’s phrase — making people masters of their own destiny — while recognizing that rural Nova Scotia still faced significant socioeconomic challenges, certain of which had not existed in the 1920s and 1930s, and certain of which might not necessarily be best addressed by what had worked in the past. As a faculty member herself, MacNeil’s vision involved closer collaboration between extension workers and university faculty. However, that model, for a number of reasons, just never clicked.

This contributed to dissatisfaction among certain Extension employees. At the same time the prominent role that the Extension Department had once played within the University had diminished. Dodaro and Pluta write that “the university increasingly removed itself from the whole process, achieving a virtually complete retrenchment 3” (2012; p.253). The increasing number of faculty and students recruited from outside the region meant that people were arriving at StFX with little or no idea of the Antigonish Movement. The Department grew increasingly marginalized, and MacNeil resigned from the Directorship in 1993.

MacNeil has not slowed down since retiring from StFX in 1996 and has remained an active volunteer. Working to establish the Bras d’Or Lake UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and supporting its maintenance is one volunteer activity that has occupied a considerable amount of Dr. MacNeil’s time. This decade-long plus investment of time and energy began in 2003 with a call out of the blue from Grosvenor Blair, a descendant of Alexander Graham Bell.

Blair was part of a group concerned about the implications of gypsum mining at the head of Baddeck Bay. The Bras d’Or Preservation Society (later the Bras d’Or Preservation Foundation and, finally, the Bras d’Or Preservation Nature Trust) was formed in 1991 and was the first land trust in Nova Scotia to hold conservation easements 4. In addition to this work, concern over potential oil exploration in the Bras d’Or Lakes prompted the organization to examine the possibility of having the Bras d’Or Lakes designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. Blair had heard that MacNeil may be a good person to enlist to move this forward. Initially the group was looking at a relatively small area, but, as they looked more closely at the criteria, it became apparent that it was a much bigger undertaking than they had initially realized. According to UNESCO 5, “[e]ach reserve is intended to fulfill three complementary functions:

- a conservation function (preserve landscapes, ecosystems, species, and genetic variation),

- a development function (foster sustainable economic and human development), and

- a logistic function (support demonstration projects, environmental education and training, and research and monitoring related to local, national, and global issues of conservation and sustainable development). Biosphere reserves contain one or more core areas, which are securely protected sites; a clearly identified buffer zone; and a flexible transition area”.

Partners were enlisted, and many miles were logged as MacNeil recruited members to the steering committee and enlisted the support of the five First Nation communities that live on the lake. In 2011, eight years after MacNeil began her work, UNESCO designated approximately 3,600 square kilometers in the center of Cape Breton as a Biosphere Reserve. This is one of 18 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves situated in Canada. All of the Canadian Biospheres are located on the Traditional lands of Canada’s First Nations.

Securing a UNESCO designation has not diminished MacNeil’s involvement. Eight years after receiving the designation, a large percentage of the population still doesn’t understand what it means. MacNeil described the confusion: “We’ve had the designation since 2011 which is now 8 years. Still people think it’s a protection thing when it’s really an education thing. It’s about people learning to live in their ecosystem. Learning to live in harmony with nature”.

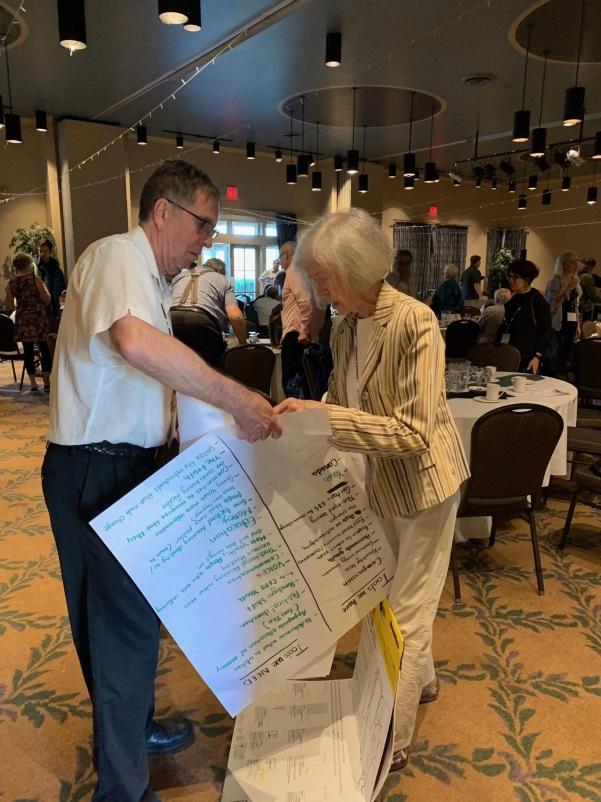

Education is a big piece of the Bras D’Or Lake Biosphere Reserve Association mandate. The Canadian Biosphere Climate Change Adaptation Forum co-hosted with The Bras d’Or Collaborative Environmental Planning Initiative (CEPI) took place in Baddeck on June 19 and Wagmatcook on June 20. As part of their welcome to Un’amaki, Forum participants joined the celebration of National Indigenous Peoples Day on Friday, June 21 in the Great Hall of Cape Breton University.

The Forum was, in MacNeil’s words, “geared toward an outcome that will provide publishable guidelines for climate change adaptation for communities”. Spokespeople representing Canada’s Biosphere Reserves along with traditional and specialized knowledge holders shared examples of successful adaptation to climate change. These are to be published and applied within the Biosphere Reserves and, ideally, in a wide range of communities.

Works Cited:

- Ludlow, Peter. “After Monsignor Coady: The StFX Extension Department 1953-2000”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsBhhk38bYw. Recorded 2018. Last accessed April 29, 2019.

- Dodaro, Santo and Pluta, Leonard. The Big Picture: The Antigonish Movement of Eastern Nova Scotia. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. 2012.

- Dodaro, Santo and Pluta, Leonard. The Big Picture: The Antigonish Movement of Eastern Nova Scotia. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. 2012.

- Victoria Standard. January 2, 2019.

- UNESCO Office in Phomn Pehn — What is a Biosphere Reserve?.